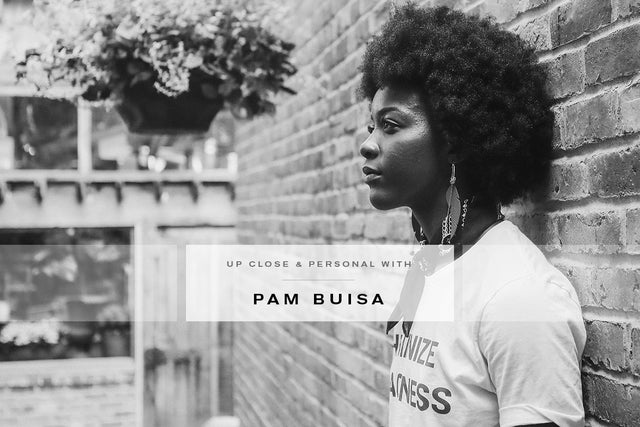

A Deep Dive into a Multifaceted Superstar: Pam Buisa

Pam Buisa is sipping a local equivalent of a double-double – the campy Canadian “institution” born out of Tim Hortons in which one bludgeons a cup of coffee with two creams and two sugars.

Sitting across from the Canadian rugby star, I allow the consumption to carry on without notice, giving her a pass. After all, everyone has at least one fatal flaw.

Even Pam Buisa.

Then again, given her every step landing just right these days, maybe Buisa is the exception (she’ll hate that line). Maybe a “double-double” from one of Victoria’s best independent coffee stops is worth trying. Who am I to question her decisions?

Sitting at a picnic table directly adjacent to the Johnson Street Bridge in downtown Victoria, the British Columbia Parliament Buildings reside in the distance. The 500-foot neo-baroque façade, complete with its patina-encased copper domes has been home to the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia since 1898.

I’ll say it here. Buisa is going to be there one day. If not, it’ll probably be just because she’s in Ottawa instead, on Parliament Hill.

Near the end of our conversation, I ask her outright.

Are you going to be our Prime Minister one day?

“Maybe.”

She smiles.

“We’ll see.”

Centennial Square is just two blocks west of where Buisa and I converse.

It was there, on June 7th, amidst the Black Lives Matter movement, where Buisa stood on a stage in front of thousands of people and helped lead a Peace Rally for Black Lives.

Buisa chanted.

“Vic Sees. Vic Hears.”

First she was a voice and then she gave a voice to others, handing the mic to anyone who had something to say.

“We are different,” Buisa says, reflecting on the rally. “We speak different. We look different. There is a huge diaspora of people and their experiences have often been suppressed. I wanted to show that we are so different and I’m going to just give you the mic because you should have the mic and you should say something.

“I wanted Victoria to see us and to hear us. It was so cool to see the unification of community. We wanted to take up space in the heart of the city and the heart of the community and show that Black Lives and People of Colour are here alongside our allies.”

That morning, Buisa, 23, called her mom, Jeannette Malonda, and dad, Pamphile Buisa, in Gatineau, Quebéc.

“I was so stressed,” Buisa recalls. She’s been a leader her whole life, but this was going to be entirely different.

The same sentiment could be said for her dad.

“Even though she assured me that it would be peaceful, I was sleepless the entire week,” Pamphile says via email. “I prayed like never before. I told her to have an inclusive message, including people from different backgrounds or stories that unique audiences can relate to.”

Then, her mom asked about her “look.”

“How are you going to do your hair?” her mom asked.

“I’m not sure…but what if I have my hair in an afro?”

“I don’t know. It might be a bit too much. Just be careful.”

Buisa thought about it. Then she decided to do it.

“I was thinking, often I’m so scared to show that I’m here and I’m different. We’re in Victoria and not a lot of people rock their afro just out there. But I know that it comes from fear and if I’m trying to fight fear, I can’t fight fear with fear. I have to overcome that.”

She donned her white boots, an all-black leather outfit and rocked her afro.

She called her parents.

“Yup. I’m doing it.”

Fellow Canadian rugby sevens star Charity Williams was inspired.

“I think it was really powerful for a lot of young, Black women to see someone like that wear her natural hair and be vulnerable, but also be strong at the same time,” says Williams, who was also a prominent figure on stage during the rally. “It was hard for her, but she knew how important it was. It’s definitely something that’s tough, but I was very proud of how she represented so many Black women.”

Then Buisa embarked on an event she will never forget – a day many years in the making.

Buisa’s parents are originally from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In search of a better opportunity, they originally moved to South Africa, where they experienced Apartheid firsthand.

“Having seen a lot of the racial injustices that were happening in South Africa, protesting and speaking out was a very scary thing,” Buisa says.

In 1995, her parents moved to Canada, settling in the Vanier neighbourhood in Ottawa.

While her parents were both professionals in South Africa and the DRC, with Pamphile Buisa having an education in horticulture and Malonda educated in computer sciences, her parents’ credentials were dismissed in Canada.

So, in Pam Buisa’s words, they “just grinded.”

“It was difficult to see how hard my parents had to work. They were so resilient. They just wanted to engage in society, but often society didn’t see them as equivalent, so they just had to work twice as hard. For me, that’s not right. I’m benefiting from their hardships. So, if I don’t put in the work, I’m not giving their hard work justice.”

From a young age, Buisa was already combining her passion for justice with her zest for sports.

Driving from one activity to the next within Gatineau, where her family moved in 2006, a young Pam would see a smokestack emitting pollutants and suggest, “If I become the mayor of this city, on the first day in office, I will close this factory.”

Amidst playing all the sports – be it ballet, swimming, basketball, volleyball, flag football, or rugby – she was a leader within her schools and her teams.

“She is always standing up for inclusiveness and she doesn’t shy away when she sees social injustice, inequality or denigration against a certain race, religion, or sexual category,” Pamphile says. “Those are the core values of Pam. She likes to voice her opinion and you will never convince her otherwise on what she believes and what is just and fair.”

It was Buisa who led her school’s social initiatives. It was Buisa who won the Lieutenant Governor’s Youth Medal while at Cégep Heritage College for demonstrating “sustained voluntary action at the community and social levels…and (showing) an inspiring attitude and a positive influence inside a group or community.” It was Buisa who initiated the first-ever Black History Month celebrations at Cégep Heritage College.

“I did everything, simply to ensure there was a BIPOC voice. I didn’t want to be the token Black person. I wanted to show that I’m multi-faceted and have different skillsets. With the support of my parents and my friends, it made it a lot easier to be in those spaces.”

Then there was rugby.

In Grade 7, a rugby coach was watching Buisa play basketball.

“I just kept on getting fouled out,” Buisa says.

He asked her if she’d be interested in trying rugby.

“I was super intimidated,” recalls Buisa, who was the only Black girl on the team and younger than most of her teammates. “But realizing that being aggressive was very much embraced in the sport and being muscular was actually attractive – that drew me to rugby.”

Coming through the Ottawa Irish, she soon flourished.

In 2013, she made the Quebec provincial team and, with her early-on ability to rally people and make things happen, she sold enough Rugby Quebec t-shirts while sitting outside Philemon Wright High School to pay her way to travel to Vancouver to play in the U18 Rugby Canada National Championships.

“After playing for Quebec, I remember our coach Jocelyn Barrieau talking about being the best you for Quebec. I’ll never forget that. It exposed me to what it means to represent more than just yourself.”

Her experience with Quebec set Buisa up to earn selection for Team Canada for the 2014 Summer Youth Olympics in Nanjing, China.

It was in Nanjing, where Canada won a silver medal, that Buisa saw her platform and her opportunity.

“Being there made me realize that when you represent your country, you have an opportunity to interact with other countries and be exposed to different perspectives, different beliefs, and different cultures. That allows me to be more informed and a more well-rounded person, which helps me better decipher what is right and what is wrong.”

It was her moment of intertwining her sport with her passions.

“Ever since then I’ve wanted to be on the national team, at the Olympics and on top of the podium. And also that experience led me to be able to speak out and fight for justice.”

It’s now been four years since Buisa joined the Canadian Sevens side in a full-time capacity, having launched her senior career in the spring of 2016.

Charity Williams, who has played in 124 career games on the World Rugby Sevens Series and has 70 tries to her name (third all-time amongst Canadians), has walked alongside Buisa every step of the way throughout her international journey, having also played with Canada at the Youth Olympics in Nanjing.

“I’m just really happy that she’s my teammate and I’m not playing against her,” Williams says with a bit of a laugh. “She’s stiff-armed me a couple times in scrimmages. I always remember those moments.”

Since Buisa made her debut on the World Series in Langford, B.C. in 2018, she has put herself into a regular role with the world-travelling side. This past season, the 5-foot-11 Buisa was at her best, playing in four of the five events, earning playing time in 20 games and starting for Canada 15 times. She also tallied three of her four career tries this season.

But then, COVID-19 struck and the 2019-20 season was, eventually, cancelled. Then, the Olympics were postponed.

That’s when everything changed for Buisa.

“So I’m like, you have all this time and you have a skill set that you know you haven’t tapped into, so what can I do to not only amplify the thoughts that I’ve always been thinking, but also amplify the voices of people who have also felt the same way.”

Buisa was put in Victoria for such a time as this.

In hindsight, maybe the “double-double” was an homage to the conversation she had with her dad many years ago.

The father and daughter were in Tim Hortons in Gatineau in the summer of 2015 and Buisa, who had been considering a variety of universities in Ontario and Quebec, had a PowerPoint presentation prepared. She was going to convince her dad of the merits of going to Victoria to pursue a national team career. Buisa didn’t have a contract with the Sevens side, but attending the University of Victoria and playing for the Vikes would put her in geographic proximity to the national team. She had a sound plan, with a way to make the endeavour financially viable.

“Knowing her personality and her seriousness in life, I had no doubt that she would handle herself very well,” Pamphile says. “So she moved to Victoria with all my blessings. But the following six months was the toughest time in my adult life. Her mother handled herself much better than I did. I cried every day, I couldn’t sleep, I lost my appetite, I lost weight and vitality and I was unproductive at work. But looking back, I think everything turned-out just great. I‘m so proud of her.”

Across the country, a 17-year-old Buisa struggled early on. She arrived in Victoria already in the middle of rehabbing a shoulder dislocation. Meanwhile, she was working two jobs, was a full-time student, was trying to figure out a way onto the national team and, on top of it all, she wasn’t really even comfortable in her own home, which was in a bit of a rough neighbourhood. Instead, she often crashed on the couch of former Canadian international superstar Magali Harvey, who was with the Sevens program at the time. But even then, she’d get woken up by Harvey’s cat sitting on her face.

“It was crazy,” Buisa says. “It was extremely difficult.”

Following her first semester at the University of Victoria, she got a message from Canada coach John Tait asking if she’d like to come to train. Within a few weeks of training, she was granted a spot within the program.

That was the dream.

It took Buisa two years to make her debut on the international Sevens circuit, but, with her parents as an inspiration, she never quit.

“They’ve gone through hard times,” says Buisa, who is now on the verge of completing her degree in Political Science with a minor in Social Justice. “So I just need to do my job to make them proud.”

Four years later, in the midst of a chaotic 2020, it wasn’t rugby that had Buisa’s name and likeness plastered across Canadian mainstream media and social networks. It was her efforts in this pandemic time in this pandemic place.

Before the Black Lives Matter movement resurged, Buisa helped created the Vancouver Island Steps Up community relief fund, which raised more than $15,000 to help local people who were struggling financially because of COVID-19.

Then, while also working as a front desk agent at the Howard Johnson Hotel, which was bought by the province of B.C. and is now being used as temporary housing for unhoused individuals during the pandemic, she found her platform within the Black Lives Matter movement.

“She is a natural-born leader,” Williams says.

Her role as a player on the rugby pitch morphed into a similar role in the community.

“I can play my best when I play like Pam,” she says. “When we need someone to bring the team forward, I’m looking to get the ball to do that. It’s to run through people and run over people. To setup my teammates. It’s to catch the ball in the air. It’s to be a presence and make way for my team.”

Like she did on the stage in front of thousands of people in Centennial Square, Buisa, who is conversationally engaged daily with local Victoria leaders – both politically and with various groups, including Indigenous leaders – is about building up people and letting them run.

“Pam is a very passionate and strong human being in every aspect of life,” says Williams, who will continue to be right by Buisa’s side, as they both steadfastly pursue the postponed Tokyo Olympics in 2021. “She’s very outspoken and she’s just somebody who can get it done. She’s consistent. She’ll bring the same energy, passion and fire everywhere she is. I’ve definitely seen her grow as a person. She’s always been the same person, but now she’s taking all her talents and bringing it to a broader audience. Everybody else now gets to experience so many facets of who she is. I think that’s where she excels – being able to help people in almost every walk of life.”

Perhaps Pamphile says it best.

“Pam has natural leadership for whatever she does whether in sport, work or school. She has a bold personality. She’s effective, self-confident, and has a social ability to inspire and encourage others, radiating both passion and love for whatever she’s involved in.”

That’s Pam.

She’s on a mission. And she’s carrying the torch.