Ædelhard Club: On becoming a gentleman

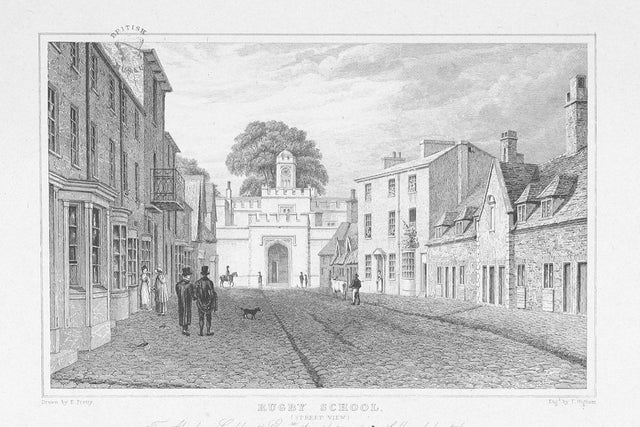

This was one of our first pieces here at Ædelhard. A piece explaining the establishment of an old Victorian-type intellectual club, and how it in part spurned the creation of our company. It’s a great glimpse into the world which existed around the time that William Webb Ellis picked up that ball and ran with it on that cold day in 1823. Rugby School is to this day a fine auld institution. The rugby posts stand proudly, surrounded by the stone buildings and archways of the school. The town of Rugby itself is proud of their roots and aware that the school is the centre of attention within their community. It’s awe-inspiring, and anyone that considers themselves a staunch supporter or expert on the game must visit the village and school at least once. Now that the World Rugby Hall of Fame is housed there, and we boast three Canadian entries (former Mens 15s Captains Gareth Rees and Al Charron, and former 15s Star and Olympian Heather Moyse), Canadians have all the more reason to step back into time and explore our rugby roots. Please acquaint (or reacquaint) yourself with On Becoming A Gentleman. As you read, please note that in these times where we are also proud to support our fantastic women in rugby, the story is not as inclusive as we’d like. Society had a long road ahead from the 1820’s to today, where we women play a much more equal role in our storied sport, and where women are making an active contribution to life at Rugby School, both as student and instructor. And rugby player:

A cultural shift took place during the Victorian era. Throughout the 19th century, a transition occurred that shifted the title of gentle folk from entitled to earned. It was the democratization of the status of gentleman.

In the early-1800s there was no standard definition of gentle folk. Many men desired to be referenced as gentlemen and yet traditionally it was royalty and those who governed that held that status. Earls, Dukes, and the royalty class earned their titles through inheritance. There were those who were born with status and those who were not. Those who were gentlemen behaved in a certain manner and dressed in a certain way, but this was not extended to the masses.

In the early nineteenth century, there was an emerging shift in power and influence amongst the population of England benefitting the mercantile and trading class. With business success came an ability to sway politics and government. Yet, still at the time, there was no status for businessmen-like owners of coal mines, railroads, manufacturing plants, steel mills, and the like.

You can imagine how the owners of coal mines, railroads and steel mills wanted to distinguish themselves from those mining the pits and manning the flames. These emerging tycoons sought the benefits that money brought. Traditionally, appointed status typically fell upon clergy, the military elite, and Members of Parliament. Business leaders knew that their influence was as powerful as those who were currently considered gentlemen and as such, what they required was a shift in societal discourse. Their first vehicle to achieve this was the private club.

Private clubs began to sprout out across England in the mid-1800s. These clubs became a place where the aristocracy could mingle with the industrial elite. Where business could blend with politics. Two famous aristocratic gentlemen clubs of the 1700s were Boodle’s and Brooks’ of St James Street in London. Membership was scarce and most often inherited. In the 1800s, however, many more clubs were founded. The Carlton Club, East India Club, Beefsteak Club, the Alpine Club, the Army and Navy Club, and The Athenaeum were several examples of clubs in London that brought together nouveau riche with those who had traditional hereditary power. Conversations and connections that occurred at these clubs benefitted those who had the money. A shift began to happen.

This activity extended outside of London as well. In the midlands, serving Coventry, Wolverhampton and the surrounding area now known as Warwickshire, several clubs emerged in prominence. One of the more secretive clubs, known as the Ædelhard Club, was founded to promote the social influence of its members. Members used its influences to promote gentleman status as a set of behaviours, not a title bestowed upon one at birth.

Throughout the 1800s, opinions differed as to what would be considered gentlemanly behaviour. Regional differences in dress, mannerisms, and expressions confounded many. It was almost an awkward dance for gentlemanly norm supremacy.

In 1832, Dr. Thomas Arnold became the Head Master of Rugby School, an elite British boarding school in the midlands of England. During his tenure at Rugby School, Dr. Arnold executed many reforms to the curriculum and administration based on the morals and code of conduct which fused religious and moral principles, gentlemanly conduct, and learning based on self-discipline. These morals were socially enforced through the “Gospel of work.” The object of education was to produce “the Christian gentleman,” a man with good outward appearance, and who was playful but earnest, industrious, manly, honest, virginal pure, innocent, and responsible. Dr. Arnold, through his work at the school and in social clubs such as the Ædelhard Club (in which he is rumoured to have been an influential member), worked to define what it meant to be a gentleman.

Outside of social clubs, sport became no small part of this social agenda. The sport of rugby, founded at or around 1823 at Rugby School, as well as cricket, rowing and polo, were designated the sports of gentlemen. The old expression rings true: “Football is a gentleman’s game played by hooligans. Rugby is a hooligan’s game played by gentlemen.” The sport was seen as having the right amount of chivalry and the right amount of barbarism. Rugby’s players’ code almost harked back to feudal England’s code of combat which was fundamentally founded in chivalry. Cricket had tea breaks (very respectable). Polo and rowing were sports of the elite public schools and colleges such as Oxford and Cambridge. Common across these sports was an adherence to the code of conduct, some say entrenched into societal discourse by Dr. Thomas Arnold.

The code of conduct was grounded in respect, chivalry, virtue, and neatness of appearance. The code at Dr. Arnold’s elite public school Rugby was in line of those fostered in private clubs such as the Ædelhard Club. The plan hatched in social clubs across England was in full swing by the latter part of the 18th century: teaching the next generation of gentle folk while changing conversations in the country’s elite social and sporting environments. This subtle yet disruptive social movement worked.

By the turn of the century, it was commonly accepted that the behaviours of gentle folk were manners as taught in England’s finest public schools like Eton, Harrow, and Rugby. If one was the recipient of a traditional liberal education, grounded in Latin, at fine schools such as these, and behaved in a manner consistent with the code, one would be recognized as a gentleman, no matter what one’s origins. England’s industrial elite could now sit at the table with the aristocrats. Power had shifted.

A lot has been lost over the last century in terms of gentlemanly behaviour. For youth to use the phrases ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ often is considered a miracle. It is so refreshing nowadays when gentle folk touch our lives. Manners of days gone by should make an appearance again. Perhaps old tricks must be made anew.