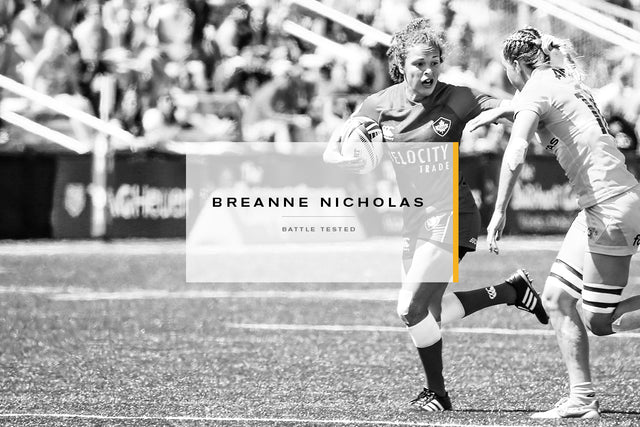

Canada Sevens Breanne Nicholas – Head Down, Fire Lit, Aim True.

Julia Greenshields knows Breanne Nicholas better than most.

So when Greenshields is asked about her Canada Sevens teammate, she explains Nicholas simply as:

“She is such a tough, bad-ass girl.”

This is true. We’ll explain why.

But first, Greenshields goes on:

“As a person, she’s so kind…selfless…and honest. As a player, I don’t think I’ve ever heard her complain. She’s resilient and she’s feisty.”

This is a story about Nicholas.

And why Greenshields is exactly right.

On December 1, 2016, Nicholas took an offload, squeezed out of the arms of the first would-be tackler, turned up field and promptly fended a hard-charging Deborah Fleming – a powerhouse of English strength in her own right – before diving across the line in Dubai for her first-ever try on the World Rugby Sevens Series.

It was a delightfully appropriate statement to the rest of the world.

I’m going to put my head down and work harder than you. I’m here to stay and I’m going to be a nuisance to the opposition in every way possible.

We’ll use Greenshields again to explain Nicholas’s game:

“Big hit. Go for the ball. Get the ball. Make a play.”

The 5-foot-4 Nicholas, who is a mainstay in Canada’s Sevens side, is a product of Blenheim, Ontario.

As a child, sports were her thing – specifically track and field and soccer. As so often happens in Canada, she didn’t grab a rugby ball until she was in Grade 9, when she joined her high school’s side before eventually joining Kent Havoc RFC. Those who knew Nicholas well probably weren’t surprised when she soon excelled at her newfound passion.

You see, away from the field, Nicholas was a rugby-type in the making.

In her elementary school days, Nicholas, her twin sister, Amber, and their younger sister Cora, worked on the neighbour’s farm, harvesting his garden. As they grew older – about the same time Breanne was finding her way into rugby’s upper echelons – the duo worked in the not-so-forgiving world of corn detasseling. It’s simple work, but hard work. In Southwestern Ontario, it’s something of a right of passage for teenagers. If you’ve done it, you know. Basically, you walk among endless rows of corn all day long, ripping the tassels off the top of the corn stalks in a long-game effort to hybridize two varieties of corn.

“It makes me grateful for what I do now because I don’t want to go back to field work,” Nicholas says.

Beyond work, school and sports were a package deal.

“My dad always said that if we got good grades, then we could play sports,” she says. “That was the deal. I don’t know if he’d actually not let us play sports, but we definitely tried hard in school to make sure.”

Nicholas quickly made a name for herself in rugby, earning a spot with Ontario’s U17 and U18 sides before getting the call to join Canada’s U20 squad for both the 2013 Nations Cup and the 2014 CAN AM Championship. In the second of her U20 opportunities, Nicholas was named the Player of the Series. However, prior to her second go-round with the U20 team, Nicholas also won gold with Canada at the 2014 International University Sports Federation (FISU) Women’s Rugby Sevens Championship in Sao Jose de Campos, Brazil.

While Sevens was new to Nicholas, the opportunity was a nod to her clearly being on the national radar.

After two years playing at Western University, in 2013 and 2014, a summertime tryout with Canada’s senior Sevens team in 2015 saw her earn an invitation to join the national team full-time.

Four years later and now well-established in the Canadian system, Nicholas looked at the 2019-20 season with great optimism. She was coming off having just helped Canada win gold at the 2019 Pan American Games, scoring once and converting twice in the final against the USA, and she hadn’t missed a World Series tournament since the end of the 2015-16 season, earning selection in 17 straight events, plus the 2018 Commonwealth Games and the 2018 Rugby World Cup Sevens. Her series debut in 2016, when she went all Breanne Nicholas and bounced out of a bed-ridden state of sickness in just two days to get on the pitch in Sao Paolo, seemed an eternity ago.

Then, in the 2019-20 season-opening tournament in Glendale, Colorado last October, Nicholas suffered a concussion that would alter the course of her entire season.

Her early attempts to return to play failed. She missed Dubai and Cape Town, but she expected she’d be ready for the series stops in New Zealand and Australia in early 2020.

She wasn’t. Upon returning to contact, she failed to move along in her concussion protocol.

“That’s when I had a full-on breakdown,” Nicholas says.

Life hit Nicholas in a way few people around her even realized.

Around the very same time a year before, her brother, Danny, unexpectedly passed away at the age of 32.

The ever-tough and fun-loving Nicholas remained on her exterior, but things weren’t okay.

“I was in a really bad place in January and February,” she says. “I tried to make it seem like I was okay, but I wasn’t.”

She sought professional support, but her own questions about her rugby career remained at the forefront. Her sister, who had also played at Western, had previously been forced to quit rugby because of concussions.

“Will I ever play again?

“I never thought about quitting. I just wanted to get better and feel better. But mentally I wasn’t okay. I’d have breakdowns at training.”

Rugby has always been an outlet from life, but in those moments, it couldn’t even be that for Nicholas.

“When I’m on the field, nothing else really matters. So it was hard mentally. I was emotional because of the concussion, but also because of what having the concussion caused.”

With her various support systems helping her navigate the early part of 2020, she finally returned to training in early February. Then, one day, she said she felt a pain in her side. She didn’t think much of it. She wanted to train. She suggested to Greenshields that it was probably just a cramp. In fact, it was appendicitis and on Feb. 14, she had surgery.

“I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re so tough,’” Greenshields recalls. “But she really is like that. She’ll run herself into the ground because she just wants to do everything to the best of her abilities for the team.”

A few days after she returned from her appendicitis, the COVID-19 pandemic forced training to be shut down, which eventually forced the cancellation of the rest of the season and, in time, the Olympics.

Several months on, Nicholas walks across a piece of driftwood on a craggy beach in Victoria. She hops off onto a nearby rock. Being near the ocean brings her joy. She reflects on her darkest days.

“You have to separate sport and life. Sport isn’t as important as your life’s well-being. If you need the help, get the help.”

Amidst the time away from a formal rugby schedule, Nicholas, who has both Black and Indigenous heritage, has had a chance to wade deeper into her identity and the racism she experienced.

“You don’t think about it sometimes, but it makes you reflect back on it. At the time, you’re like ‘whatever.’ People are like, ‘Can I touch your hair?’ or ‘Is it real?’ or ‘Have you ever straightened it?’ and stuff like that. It’s mostly about my hair. But even while I was in University, someone used the N-word with me.”

Coming from a multiracial background has put Nicholas in a variety of unique conversations – sometimes challenging, sometimes awkward, and sometimes fruitful.

“Embrace who you are,” says Nicholas, who recently took part in a photoshoot atop the Yates Street Parkade alongside fellow teammates Charity Williams and Pam Buisa. “It doesn’t matter what other people view you as. This is who you are.”

Sitting at a picnic table on a windy afternoon at Saxe Point, Nicholas can look back at what was her most challenging season to date, but also look forward to a second chance. With the Olympics now scheduled for 2021, a healthy Nicholas, who “feel(s) the best I’ve been,” has a fresh slate. The podium – the same one she saw her teammates stand upon in 2016 when Canada took bronze in Rio – motivates her.

While the Sevens schedule is very much in flux, this is a time when Nicholas might shine brightest.

When training restarts with the team in August, she’ll be Breanne.

“Anytime we’re doing fitness testing, she’s the person I’m trying to keep up with,” Greenshields says. “And she never complains – ever, ever.”

On those challenging days, she thinks about her past.

“You’ve signed up for this. You like this. I know it’s a shitty day, but it could be worse – you could be in the corn fields.”

And sometimes she’ll think about Danny.

“That’s also a motivation for me to do what I love because who knows when your life can end.”

Then, Nicholas will put her head down and grind.

That’s the story of the bad-ass girl from Blenheim.