A Canadian Judge usually thick in the mix of rugby judicial hearings for World Rugby

Written By: Doug Crosse

Photos By: Ruck Science/I Expert Magazine

Think of some of the most titanic battles between major rugby foes over the last decade. Now think of the variety of plays that blurred the lines of fair play and resulted in yellow or red cards, or if no cards, resulted in post-match citings. Did you know that often it was a Canadian that was called upon to resolve the questions of law surrounding suspensions, mitigating circumstances, and the meting out of punishments?

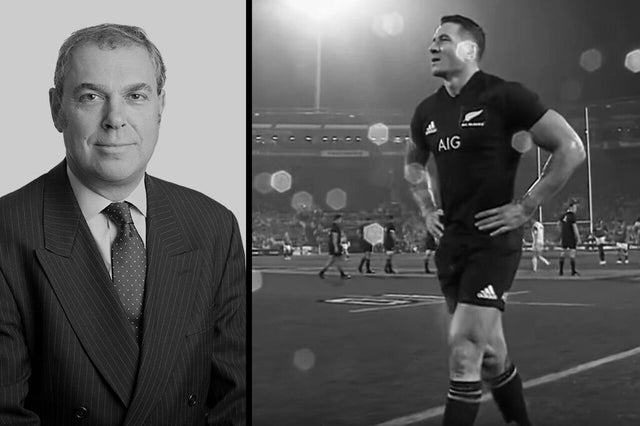

Graeme Mew is an Ontario Superior Court of Justice judge who, when he hangs up his black robes at the end of each week, often sits in judgment of players involved in key matches on the rugby calendar. When Sonny Bill Williams and the New Zealand team management disputed his four-match suspension for a shoulder charge in the second match of this past summer’s Lions tour, it was Mew who heard legal arguments on what games could be included to allow the centre to return in time to take on Australia in a key Bledisloe Cup test match.

In this instance, World Rugby’s judicial panel had decided that SBW’s fourth suspension match, an All Blacks warmup match against Counties and Taranaki provinces, was not a “match” because the All Blacks played against Counties in the first half and Taranaki in the second.

In the ruling for the appeal committee, Mew, who chaired the trio, along with Shao-Ing Wang (Singapore) and ex-Springbok player Stefan Terblanche, determined the game fit the bill because it was nevertheless “a game in which two teams compete against each other,” albeit that the All Blacks’ opposition changed in the second half.

In the ruling for the appeal committee, Mew, who chaired the trio, along with Shao-Ing Wang (Singapore) and ex-Springbok player Stefan Terblanche, determined the game fit the bill because it was nevertheless “a game in which two teams compete against each other,” albeit that the All Blacks’ opposition changed in the second half.

The decision was not universally well-received. Even some World Rugby officials criticized it. “It really highlights the independent framework that we work within,” said Mew in an exclusive interview with Ædelhard Rugby. He explained that while he is appointed by World Rugby, the governing body ultimately does not have any say or control in the rulings judicial officers are asked to make.

It is just one of many memorable judgments Mew has made since answering the call of the then International Rugby Board in 1999, right through to today’s World Rugby organization.

Originally from England, Mew, a civil litigator for nearly 30 years, became a permanent resident of Canada in 1985 and practiced on both sides of the pond for a couple of decades. In that time, he served as an honorary legal counsel to Rugby Canada, and was President of the Toronto Nomads rugby club. Extensive legal work in sport, including ruling on Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson’s 1999 reinstatement bid, ultimately got him involved with the early days of the International Rugby Board’s anti-doping program.

Rugby was seeking inclusion into the Olympic family of sports, which would require an extensive anti-drug program. Through a recommendation from Rugby Canada’s IRB board member Alan Sharp to then IRB chairman Vernon Pugh, Mew was welcomed into a role on an “anti-doping advisory committee,” a role he continues to fulfill to this day.

“We helped to set up an Olympic compliant doping program,” recalls Mew, “which turned out to be an important factor many years later for the inclusion of rugby 7s in the Olympics.”

That led to Mew hearing rugby related doping cases, and ultimately to rugby discipline work.

Mew admits it was work he looked forward to through his love of sport. “I wasn’t a very good rugby player, but the ability to use my legal skills within rugby was appealing,” he says. “Because I was Canadian, that overcame a lot of neutrality issues.” He says a lot of people from New Zealand, Australia, and the UK ran into neutrality issues, as often it was players from those countries involved in a dispute.

“Being a Canadian was good because when it came to appeals at a World Cup there were usually very few conflicts,” he remarks with an ironic chuckle. Despite his steadfast Canadian-ness, his British background (and accent) came to the forefront when Mew was hearing an appeal of a stamping incident by Australian Captain James Horwill during a British and Irish Lions tour.

“World Rugby announced a Canadian would be hearing the appeal (Horwill had been cleared by a New Zealand Judicial officer, prompting an IRB appeal), but a Sydney paper ran a headline stating 'He’s Not Canadian - He’s a Pom' with the resulting article inferring the fix was on!

“Luckily I didn’t see that article prior to the hearing,” he says with a laugh.

Despite the pressure, praise was heaped on Mew for his work in the highly controversial hearing, with the UK’s Guardian saying “Mew, whose parameters were narrow – he was effectively restricted to checking whether Hampton had followed the correct procedure as laid down by the rules and whether he agreed with the verdict was immaterial – is to be commended for resisting what Australia saw as an invitation to ban Horwill.”

How Mew gets involved in hearings is a result of either a red card being issued (resulting in an automatic judicial hearing), or a yellow card ruling that has been heard by a Citing officer, but where one or both sides have requested an appeal, or via a separate citing by the Citing officer watching a game. Lest you think this is all done in the swishy confines of a five-star hotel, more often than not, these are video conference hearings that might be heard at Mew’s dining room table, thousands of kilometres away from the participants.

“Sure, I do get to travel at times and see some of the big games, but a lot of it is done through video conference remotely,” he says.

Time is often the biggest issue, as hearings have to be done quickly, taking into account teams flying out soon after matches, making for 24 to 48 hours windows, and sometimes much less.

Formerly a solo role, now the judicial officer is part of a trio of officers, as well as judicial appeal committees, which are also three-person units.

Some of the higher profile cases he has heard included the overturning of Scottish duo Jonny Gray and Ross Ford at the 2015 World Cup and the banning of England coaches Graham Rowntree and Andy Farrell from the tunnels and changing room areas because of halftime off-field backchat to the referee in England’s loss to Australia at the 2015 tournament.

Mew admits that the access the public has to video clips online and also the viewing of incidents in excruciating frame by frame detail allows for a lot of second-guessing on decisions.

“There are things that are pretty awful to the untutored eye,” offers Mew. “In large measure, because rugby has precise laws and severe sanctions, that if you think of rugby and compare it to gridiron football where players have protection and there are massive hits, (Rugby) looks pretty good in comparison to some of those sports.

“That’s why it is important to have a rugby perspective when you judge these things.”

Over 17 years, Mew admits he has heard a gamut of explanations for a split second lapse of judgment on the pitch. And while he won’t go so far as to say some explanations defy logic, he clutches to his legal robes firmly in saying everyone is allowed a defence.

“You get people reinterpreting what has happened in a way that is favourable. It’s like anything else, people are entitled to raise a defence,” Mew offers. “I have to say with rugby generally, in a case involving foul play they usually put their hands up and admit to it.

“The issue usually is: was it intentional, was it reckless, or ‘I admit I did something wrong, but it should be treated at the low end rather than the mid or high end of the scale.’ ”

Mew admits there have been times that a ruling has been overturned due to extenuating circumstances or explanations. “You don’t blame people for putting their case in the most favourable light.”

Overall, he says he enjoys it, pointing out that judicial officers do their work as volunteers. “You wouldn’t do it if you didn’t enjoy it,” he says frankly. “The enjoyment still outweighs the discomfort of being criticized for doing your best.”