Warren Abrahams – Challenge Accepted for this Talented Coach

Captain Abby Gustaitis is succinct when describing the first month with Warren Abrahams as an assistant coach with USA’s Women’s Sevens program.

“Absolute madness. Pure frustration.”

When Abrahams reads that, he’ll laugh. Then he’ll probably throw a wrench – like, a literal wrench – into the next drill and make his athletes toss it around looking to get the “ball” to space.

Okay, so maybe it wouldn’t be a wrench (or maybe it would), but here’s the picture from USA’s practice facility in Chula Vista, California:

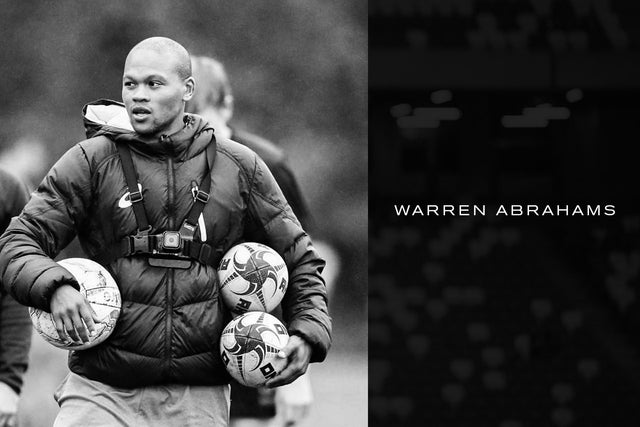

Abrahams walks around the rugby pitch holding a variety of balls – be it a tennis ball, a handball, a basketball, or even, maybe, a rugby ball. At any moment, he inserts a new ball, with a new set of rules, into an already active drill. It’s on the athletes to sort through the challenges.

“My style of coaching is very messy, chaotic, and with a lot of problem-based learning,” Abrahams says. “You have to find your own solutions and suddenly you’re making a lot more decisions and you’re making a lot more mistakes. You’re uncomfortable. I’m challenging you from a cognitive point of view to really think about why you do what you do on the field.”

Early on, Gustaitis and her teammates just saw the chaotic part.

It’s like this:

They’re playing a normal game. It’s live tackling. They’re playing with an actual rugby ball. Then, Abrahams tosses in a tennis ball and takes the rugby ball. The players kind of pause, wondering what he wants them to do next. He just looks at them.

“Why are you stopping?”

With a new ball in play, now it’s no longer live tackling, but just wrapping up. For a moment, the players ask “why?” – verbally or, sometimes non-verbally (an exasperated Gustaitis may have allowed herself the occasional eye-roll).

“Just explore the options available,” Abrahams says. “We’ll talk about it later. You have to ignore things you can’t control.”

Gustaitis reflects back on those early days.

“Thrown into that was very challenging and frustrating. I mean, how is playing with this blown up Pilates ball helpful? And he’d be like ‘you don’t need to know everything’.”

Abrahams was building a team of problem-solvers.

“Play is the highest form of research and it’s about solving complex problems and being adaptable and creative,” Abrahams says. “You look across that team and so many players came from other sports. Their rugby brains were uncluttered. It was a beginner’s mindset and with that springs creativity.”

On the first day with the team, in September 2019, Abrahams walked into a meeting with the squad. The chairs were all in tidy rows. Gustaitis sat in the same spot she had been sitting in every day for the last three years. Abrahams saw potential for growth.

“I definitely would come in and move the chairs just to mix it up a little bit,” Abrahams says with a smile. “It was a lot of fun for me from a coaching perspective because I challenged them. The players were incredible people, so I knew I could have a lot of fun with them in terms of how to maximize their human potential.”

Nearly a year removed from those early days with Abrahams, Gustaitis still gets a little fired up chatting over the phone from her home in San Diego.

“We’d come in and there’d be cards on the floor or a tic-tac-toe board on the floor and the chairs are all messed up,” she says. “Then he’d have us play a game and part way through he throws in some rogue rule that changes everything. We’d all be bitter for the rest of the day, and he’d be cracking up.

“We got used to it eventually, but I still got worked up unnecessarily by his rule changes.”

This is the picture Abrahams painted during his first month in California.

“I just went in like a steamroller,” he says.

Then, after four weeks with the team, he explained himself.

“I presented my values, philosophies, and principles from a coaching point of view. I contextualized some evidence and only then did they realize the method to my madness.”

The South African Abrahams hails from the suburbs of Cape Town.

When he was young, he lived on the premises of the Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison – the facility where Nelson Mandela was transferred after 18 years of imprisonment on Robben Island. Abrahams’ father worked at the prison and Abrahams’ family lived atop the hill, segregated from his father’s white co-workers during the apartheid era.

“I connect a lot with my upbringing as a child and how we had to be very creative with adversity,” Abrahams says.

“It was tough and it brought some very challenging moments. It was very segregated, but that’s all that I knew. But I’m grateful for my upbringing. It shaped me as a person. I’m grateful for the adversity I faced.”

Abrahams became a creative problem-solver. He was the one coming up with games to play in the neighbourhood streets and spurring on other ideas for creative play.

Then, there was the moment.

“I can still see it.”

It was the moment when, in 1995, Nelson Mandela handed the Webb Ellis Cup to South African captain François Pienaar.

“That’s the moment that created this dream for me. I wanted to coach South Africa or play for South Africa. I had no concept of it all at the time and what coaching was, but the feeling really excited me.”

Abrahams carries a picture of the moment with him wherever he goes. He calls it his “performance picture.”

“This is the picture that ultimately provided me with this crazy dream that I’m doing today.”

With this dream in his mind, he entered the foray of post-apartheid South Africa when, in 1996, an 11-year-old Abrahams was one of the first four Persons of Colour to begin attending Zwaanswyk Primary School.

Then, years later, after his family had moved to Kraaifontein, he transferred to Monument Park High, where, in 2000, Abrahams – now a burgeoning rugby star – became the first-ever Person of Colour to represent his school’s 1st XV side.

His success on the field eventually translated into a scholarship at Stellenbosch University.

After three years at Stellenbosch, which was followed by an 18-month stint working with the academy at Durbanville Bellville Rugby Club – where he had previously spent time as a player – Abrahams moved to England in 2007 to pursue a coaching career.

“If your dreams don’t scare you, they’re not big enough,” Abrahams says, looking back on his coaching endeavours and his move to England without a job in place or so much as a plan.

It was in England where his coaching approach continued to develop.

After various opportunities as a sports teacher and a rugby coach, including an 18-month run as the head coach at Redingensians Rugby Club, Abrahams eventually found his way into the Harlequin Football Club. There, his first opportunity was as a social inclusion officer.

“My job was to use rugby as a vehicle in disadvantaged inner-city areas,” he says. “The purpose was to reduce anti-social behaviour.”

In soccer-mad England, Abrahams quickly learned rugby wasn’t the sport of choice amongst most of the kids he was set to work with. Abrahams’ creativity – no doubt harkening back to creating games in the streets of Cape Town – came to the forefront. He combined soccer with rugby. It was ball-in-hand passing, but forward passes were allowed. You get the idea. It was different balls in play and unique rules.

“You had to really think differently about the traditional way of coaching the game,” Abrahams says. “That’s where this love of play comes from. When I’m authentic with myself and I’m in this space, that’s where my creativity comes from.”

Abrahams moved into an academy coaching role with Harlequins before earning the head coaching role with the Lithuanian Men’s Rugby Sevens team for the 2014-15 season. Following that, he joined England’s Sevens setup as an academy coach. From there, he worked with Germany’s Men’s Sevens side for four months in 2019 as the head of skill development before ultimately taking the assistant coaching role with the USA’s Women’s Sevens team.

And all Gustaitis wanted was to know “why.”

“I wanted to know the reason behind everything and I couldn’t find the value in it.”

And Abrahams just wanted to know her “why.”

In one of their first meetings, Abrahams asked her outright: “Why do you get out of bed each morning? Why do you do what you do?”

It was the start of sorting through her own “why.” That’s what Abrahams desired.

“My why is to inspire and develop people,” says Abrahams. “That’s why I coach.”

For Abrahams, it’s about the people and the relationships.

On the first day with the Eagles, he was appalled at the idea of being called “Coach” or “Sir.”

“Never call me that,” he says, recalling that moment. “I don’t want a hierarchy. I want to be able to have conversations where we’re both on the same level and we’re both here to grow and make each other better. I didn’t want to have that level of hierarchy. That’s not the way I coach. I want people to be comfortable around me and be authentically themselves. I will challenge them incredibly hard and I’m sure they will challenge me.”

During the Captain’s Run prior to this past year’s season-opening World Rugby Sevens Series stop in Glendale, Gustaitis figured it out. The coaches were giving the players potential game scenarios and she was solving problems almost instinctively.

“I realized that Warren had really set us up for success and had really enabled our problem-solving skills,” she says. “That helped us really think on the spot and execute, which was really cool.”

The Eagles won the tournament.

Now, there was proof.

In Dubai, the USA took home bronze, but the Americans fell short of the semifinals in each of the next three tournaments. However, Abrahams wasn’t disappointed. He was excited for the future.

“In a way, I was grateful that we could go through these tough times. I just think these tough times make you stronger as a team and bond the team together.”

Amidst the ramifications of COVID-19, the season came to a halt before he could see the fruits of their trials. Recently, with USA Rugby struggling financially, Abrahams was released from his role with the team.

Once again, Abrahams has been flung into the unknown, which is exactly where he thrives.

“I obviously get excited about uncertainty. I definitely perform at my best when I’m in that chaotic state of mind.”